MUSIC FOR FEBRUARY 20, 2022

Organ Voluntaries:

- Soliloquy - David Conte

- A Trumpet Minuet - Alfred Hollins

Anthem:

- Love Bade Me Welcome - David Hurd

Fraction Anthem

Hymns:

- 391 Before the Lord’s eternal throne

- 606 Where charity and love dwell

- 700 O love that casts out fears

- 306 Come, risen Lord, and deign to be our guest

- 490 I want to walk as a child of the light

by Donald Meineke

Many of the great works of art – whether musical, visual, or written – are sacred in their subject matter. Yet even when its genesis is of a sacred institution, they are oft equally beloved and hold significant influence within secular audiences as well.

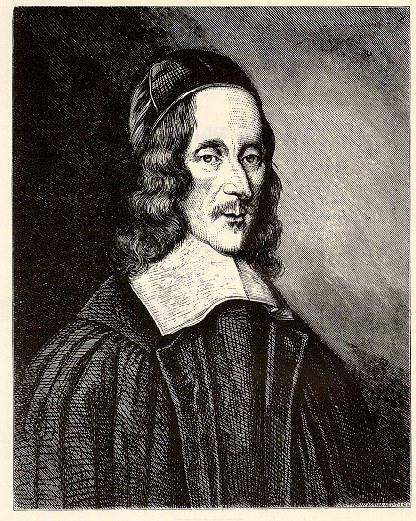

George Herbert (1593-1633) is a perfet example as such.

A Welsh-born poet and priest in the Church of England, Herbert's passionate and elegant writing inspired the likes of Henry Vaughan, Richard Crashaw, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Emily Dickinson, T. S. Eliot, Elizabeth Bishop, and even Robert Frost. Born into a powerful and wealthy family, after the death of his grandfather and father, Herbert’s mother (a notable figure in her own right) moved the family first to Oxford, then to London. It was there Herbert attended Westminster School, and later Trinity College, Cambridge. It was 1620, while at Cambridge, when Herbert was appointed oratory for the University, and through his writings, letters, and speeches eventually attracted the attention of King James I.

Shortly before Herbert’s death, he sent a literary manuscript to his friend Nicholas Ferrar, reportedly telling him to publish the poems if he thought they might "turn to the advantage of any dejected poor soul", or to burn them otherwise (dramatic, like any poet). In 1633 all of his English poems were published in The Temple: Sacred Poems and Private Ejaculations, with a preface by Ferrar. The book went through eight editions by 1690.

All of Herbert's poems center religious themes and are metaphysical in character. In "The Windows", for example, he compares a righteous preacher to glass through which God's light shines more effectively than in his words. Commenting on his poetry later in the 17th century, Richard Baxter said,

"Herbert speaks to God like one that really believeth in God, and whose business in the world is most with God. Heart-work and heaven-work make up his books".

The profound nature of George Herbert’s writings influenced English culture throughout the civil war of the mid-17th century and through The Restoration period of the 1660s. Barnabas Oley elevated him as the pinnacle of a “primitive…heavenly soul” and the model of how an ideal priest (and thus, Christian) should live: “a person of charity, a lover of traditional, time-honored worship, church music and ceremonies, and a master of 'modest, grave and Christian reproof.'” Herbert’s saintly reputation, which had grown larger than life by the end of the 17th century due to the popularity of his poems, had a significant influence on what became the standard of English culture and character. Izaak Walton wrote that the ideal Englishman, like George Herbert, should be “wellborn but socially responsible, educated but devout, experienced in the ways of the world but fully committed to the ways of the church, and knowledgeable about both the pains and joys of spiritual life.”

This week’s Anthem is a setting of Herbert’s “Love Bade Me Welcome” by the African-American composer and church musician, David Hurd, who currently serves as Organist and Director of Music at The Episcopal Church of St. Mary the Virgin in Times Square (affectionately referred to as “Smokey Mary’s” for the amount of incense used at each of their liturgies).

The marriage of Herbert’s Shakespearian poetry and Hurd’s gentle jazz chords makes for a magical affect and beautifully captures the intimacy of the text. A quick overview of the composer and author indexes in the back of The Hymnal ’82 will show a significant number of hymns and service music pieces by David Hurd, and a number of texts by George Herbert set as hymns by various composers. Vaughan Williams famously set five of George Herbert’s poem in his collection Five Mystical Songs. You can listen to his setting of “Love Bade Me Welcome” for baritone solo and choir in the video to the right.

You can also explore an online collection of George Herbert's works to the left, or clicking here.

Recent Posts